This post is also available in the following languages: Portuguese.

On the last article we have learned how we can prevent some Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks by using proper sanitization techniques on our web server. Now, let’s take a look at another vulnerability that also can cause problems on web pages that are not complying with the adequate security methods.

💡 If you did not read the previous article on this series, “Secure GET and POST requests using PHP”, I suggest you to do, as some knowledge on what are HTTP Requests, and how they do work, may be required in order to understand the following concepts — and, also, it can help you to increase your webpages’ security.

Introduction

Let’s investigate another one of the most common web vulnerabilities: the Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF), that tricks unwary users by making them execute unwanted actions on other web pages that they are already authenticated.

For a better illustration on the problem, let’s suppose this scenario: you are logged in on your bank’s account, which web server is not aware of best practices on web development; you noticed a strange transaction involving a person or a company you never heard about; on another browser’s tab, you search for their name, and accessed their website. Now, even if you did not authenticate or connect to your bank’s account into this unknown web page, and did not use a (secure) third-party challenge-response systems, our fictional malicious web page may already change your password, transferred your funds, or made a purchase using your credentials.

Sounds scary, right? Even that most modern browsers are committed to create “sandboxes” and limiting cookies’ usage that are not on same-site’s policy, there are many users on the world wide web using outdated web browsers, and clicking on every link that pops up on their monitors — most of them claiming that the user is a winner for entering the site on this specific date and time, or for completing a survey that they did not even hear about.

Tin can conversation. Designed by Wannapik.

In the past, some of the most accessed websites on the internet had suffered some sort of attacks related to CSRF, like Facebook, Netflix, Gmail, YouTube, and the New York Times, but also web applications, such as Mozilla Firefox and the Apache HTTP Server. According to this paper, many of them have already solved the problems, and others, thanks to the open developer community, fixed it as well.

By performing unwanted functions on legitimate user’s session, those bad agents use their web links to initiate any arbitrary action they want on our website, which had already validated user’s session cookie, and have it stored. That’s the worst part on XSRF attack: it does not solely rely on the website’s administrator behalf, it depends on how browsers work, and on users’ behavior too.

How CSRF works

Let’s revisit our example of the malicious page that performed an attack without the user’s knowledge.

The first condition to the CSRF attack successfully works is a situation where the legitimate user is logged in on a trustful website, by keeping a session information such as HTTP Cookies, that also ensures shorthand verification of the users’ credentials, so they don’t need to inform their username and password on every request to the web server.

According to MDN Web Docs, HTTP Cookies are typically used to tell if two requests came from the same browser. Also, they remember stateful information for the stateless HTTP protocol, or encrypted HTTPS protocol.

The second condition is a request coming from a malicious website that makes the user’s browser send a request to the web server where the user is previously authenticated, by doing a GET or POST request. It can be done, for example, by creating a web form, using HTML, whose target page is an unsecure web page on the trustful server.

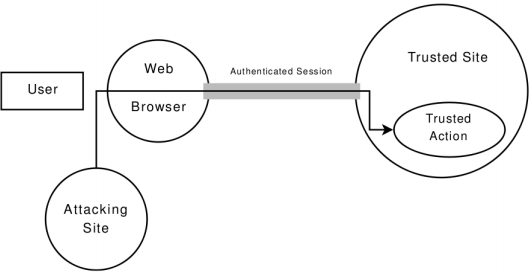

In simple terms, the Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attack forges the request that is being sent to a trustful web server, so it is “crossing sites”. The following figure explains how does the CSRF attack work: the attacking site uses the users’ authenticated session on the web browser in order to execute a trusted action on a trusted website.

Image: Souza, 2009.

For the purposes of this article, we will not cover this method on real-world applications, as our goal is not exploit any service, but, instead, to develop better implementations for the web.

Example #1: HTTP POST method

If the target page isn’t CSRF-protected, those bad agents can successfully do whatever they want using the user’s credentials. For example:

<html>

<body>

<form id="evil-form" action="http://my.trustful.bank/transfer?amount=123&account=stevie" method="POST">

<button type="submit">Click here</button>

</form>

</body>

</html>

In this example, assume the page does really exist on the internet, and so the trustful.bank uses an HTTP request to send the amount of 123 dollars to a client identified as stevie, on the page /transfer-funds.

💡 This is not a good practice, so I am sure your (real) bank is secure, and protected against it. If they are not, like any other web server, the consequences would be devastating, and it may cause some legal issues, as they wouldn’t be complying with most of the Data Privacy and Protection Regulations, such as GDPR 🇪🇺 and LGPD 🇧🇷, nowadays.

Example #2: Automatic behavior

Those bad agents don’t even need the user directly interacting with the submit button in order to achieve the sending result. They could, for example, change it to an onload event that fires whenever the user’s browser renders the page, like this:

<html>

<body onload="document.getElementById('evil-form').submit();">

<form id="evil-form" action="http://my.trustful.bank/transfer" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="account" value="stevie"></input>

<input type="hidden" name="amount" value="123"></input>

<button type="submit">Click here</button>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Also, many web servers allow both HTTP GET and POST requests, so CSRF attacks could probably work on both of them.

Example #3: Without web forms

It goes even worse, as bad agents are not limited to the HTML web forms. They can use, for example, a simple img tag, like this:

<html>

<body>

<img src="http://my.trustful.bank/transfer?amount=123&to=stevie" />

</body>

</html>

This attack can also force a user to follow a redirection, by inserting it on the httpd.conf or .htaccess file on their web server, like this examples taken from “XSS Attacks: Cross Site Scripting Exploits and Defense” (2007) book:

Redirect 302 /a.jpg https://somebank.com/transferfunds.asp?amnt=1000000&acct=123456

It would produce a request as the following one:

GET /a.jpg HTTP/1.0

Host: ha.ckers.org

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows; U; Windows NT 5.1; en-US; rv:1.8.1.3) Gecko/20070309 Firefox/2.0.0.3

Accept: image/png,*/*;q=0.5

Accept-Language: en-us,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate

Accept-Charset: ISO-8859-1,utf-8;q=0.7,*;q=0.7

Keep-Alive: 300

Proxy-Connection: keep-alive

Referer: http://somebank.com/board.asp?id=692381

And the following server response:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Date: Fri, 23 Mar 2007 18:22:07 GMT

Server: Apache

Location: https://somebank.com/transferfunds.asp?amnt=1000000&acct=123456

Content-Length: 251

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//IETF//DTD HTML 2.0//EN">

<html><head>

<title>302 Found</title></head><body>

<h1>Found</h1>

<p>The document has moved <a href="https://somebank.com/transferfunds.asp?amnt=1000000&acct=123456">here</a>.</p>

</body></html>

In this example, whenever the web browser performs the redirection, it will follow back to the informed location with the HTTP Cookies intact, but the referring URL may not change to the redirection page, what makes it even worse, because the user may not easily detect on referring URLs.

Who could imagine a single line could cause so much trouble, right? So, please remember: internet security is never too much, so there is always something new to learn and to apply.

CSRF and/or XSS attacks

The Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and the Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks share some things in common, but they are not the same. Also, they can be used and implemented together.

An example of this combination was the “MySpace Worm” (also known as “Samy worm”, or “JS.Spacehero worm”), developed by Samy Kamkar, then a 19-year-old developer, in 2005, who created a script by adding a few words that infected some people’s profiles to make him friends with, on this social network, but then quickly spread out of control, and he hit almost a million friend requests.

Part of Kamkar’s MySpace profile showing how many friends he had after his script, on 2005. Image: VICE.

Although its attack was ultimately harmless, a bad agent could have injected malicious code that would compromised the whole web server, if no one had noticed or taken the threat seriously.

💡 The Cross-Site Request Forgery is also known as XSRF, as well as CSRF, following the acronym for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS). The probable reason for this one is to avoid the confusion with Cascading Style Sheets, used for stylize web pages, whose acronym is CSS too.

How to prevent CSRF attacks

So, how we can prevent CSRF attacks? There are some things we need to do:

1. Keep your web browsers up-to-date

You’d be surprised on how many users are still using outdated web browsers and applications on their daily basis. The reasons for it are uncountable, such as the lack of information (on how to do it, and why), the compatibility with a specific version (there are many situations where the retro-compatibility doesn’t exist), or even the specifications of their contracts on their companies’ behalf — and I am not talking just about web browsers.

As a user, the first measure to take is to keep your web browser updated to the latest version. The most used applications make use of WebKit, Gecko, or other browser engine, that has been currently developed and supported by the open community of developers. They are aware of these issues, and committed to solving these problems in a short term. Some of these companies behind major web browsers also have “bug bounty programs”, so they reward security researchers who can find a unique bug that may compromise user’s data and privacy.

If you are a developer, you should alert your users that outdated application may cause some problems, including CSRF attacks, and they may be exposing their personal data to bad agents on the internet. As a bonus, this practice helps you to deliver better user experience, as updated browsers also include new functions and APIs that enhances the usability on many websites.

By the way, recently, Google and Mozilla have announced several improvements on the security of their browsers engines, such as the “privacy sandbox”, better HTTP Cookies policies, and JavaScript blocking mechanisms.

2. Check the HTTP Referrer header

Most requests on modern web browser include two metadata that can help us to validate where the source is: the Origin and the Referrer header information.

As a developer, you can check whenever a request is made to your web server if the Origin and Referrer header data came from the same site. If it does not, you can ignore it, and don’t proceed any functions from this Origin.

Unfortunately, there are few situations that it won’t be possible, and you may potentially block legitimate requests coming from users behind a corporate proxy or other similar features. Also, there are many ways to forge these headers’ information, therefore many authors say it could be not the best way to protect web servers from CSRF attacks.

3. Implement SameSite attribute

The SameSite attribute (RFC6265bis) can really help us by mitigating CSRF attack, because an unauthorized website would not complete their request into our web server if they’re using a cross-site request.

In order to make our HTTP Cookies restricted to the same-site location, we can implement this attribute by setting it to the HTTP response header. So, our HTTP Cookie can be restricted to a first-party or same-site context. For example:

Set-Cookie: TOKEN=1bf3dea9fbe265e40d3f9595f2239103; Path=/; SameSite=lax

According to the MDN Web Docs, the SameSite attribute can accept one of three values:

- Lax — default if the

SameSiteattribute is not specified; HTTP Cookies can be sent when the user navigates to the cookie’s origin site. They are not sent on normal cross-site subrequests (for example, to load images or frames into a third party site), but are sent when a user is navigating to the origin site (for example, when following a link). - None — HTTP Cookies will be sent in all contexts, and can be sent on both originating and cross-site requests. This should only be used in secure contexts, like when the

Secureattribute is also set; - Strict — HTTP Cookies can be only to the same site as the one that originated it.

💡 If you’re dealing with personal sensitive data, such as the ones used for users’ authentication, on your web server, you should set a short lifetime for the HTTP Cookies. Also, you should set the

SameSiteattribute toStrictorLax, so an unauthenticated request would not be effectively served to the web server.

Notice that you should use the SameSite attribute along with an anti-CSRF token, as some HTTP Requests, specially the GET, HEAD and POST methods, will be executed even if the request was not allowed, in some circumstances, and should return an HTTP error code in response. Anyway, a simple request was made and executed on the server-side. Fortunately, there are other ways to solve this, like using along with a random value generated by a complex and secure mathematical method.

4. Add random tokens

One of the most common methods of CSRF mitigation is by using an anti-CSRF token, a random, secret, and unique token sent on requests to the web server. Whenever the request is made, the web server could check for this data: if they match, then it is allowed to continue with the processing; if they not, then the request can be rejected.

This token can be generated for each request, stored on the web server, and then inserted on the client’s request — directly on the web form, or attached to the HTTP request —, so it will be possible to detect requests from unauthorized locations to our web server.

The bad agents can’t read the token, if used along with the SameSite attribute, and they can’t proceed in any function on our website if they don’t have the token matching to the one the web server previously set to this specific request.

This can be done by specifying an anti-CSRF token, on the same site as the trustful server, and including it to a new HTML web form, like the following one:

<html>

<body>

<form id="good-form" action="http://my.trustful.bank/transfer" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="token" value="1bf3dea9fbe265e40d3f9595f2239103"></input>

<input type="text" name="account" value="stevie"></input>

<input type="text" name="amount" value="123"></input>

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

</body>

</html>

On the client-side, we can set an anti-CSRF token in PHP, like this one:

<?php

$_SESSION['token'] = bin2hex(random_bytes(16)); // 1bf3dea9fbe265e40d3f9595f2239103

?>

Still on the client-side, if we are using JavaScript, we can add an anti-CSRF token, and send it as an X-Header information on a XMLHttpRequest. For example:

var token = readCookie(TOKEN); // Get the HTTP Cookie that we previously set, identified as "TOKEN"

httpRequest.setRequestHeader('X-CSRF-Token', token); // Then, send it as an "X-CSRF-Token" header information

Next steps 🚶

As mentioned before, internet security is never too much, so there is always something more to learn and apply. In order to build safer applications, be sure to follow the next article on this series, and read the further references to get more details about the best practices on web development.

If you have any questions or suggestions on how to build more secure applications, share it in the comments. 📣

References

[1] Zeller, W., & Felten, E. W. (2008). Cross-site request forgeries: Exploitation and prevention. Bericht, Princeton University. https://www.cs.memphis.edu/~kanyang/COMP4420/reading/csrf.pdf.

[2] Souza, J. (2009). Cross-Site Scripting & Cross-Site Request Forgery. Brasília, Universidade de Brasília. https://cic.unb.br/~rezende/trabs/johnny.pdf.

[3] Seth Fogie, Jeremiah Grossman, Robert Hansen, Anton Rager, and Petko D. Petkov. XSS Attacks: Cross Site Scripting Exploits and Defense. Syngress, 2007.

[4] “Cross-Site Request Forgeries and You”, from Coding Horror: https://blog.codinghorror.com/cross-site-request-forgeries-and-you/.

[5] “Using HTTP cookies”, from MDN Web Docs (Mozilla Developer Network): https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Cookies.

[6] “CSRF”, from MDN Web Docs (Mozilla Developer Network): https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/CSRF.